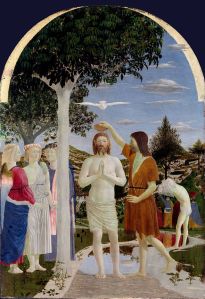

EL BAUTISMO DE CRISTO (PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA)

El bautismo de Cristo (Piero della Francesca)

| EL BAUTISMO DE CRISTO (BATTESIMO DI CRISTO) |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| AUTOR | Piero della Francesca, h. 1450 | |

| TÉCNICA | Temple sobre tabla | |

| ESTILO | Renacimiento | |

| TAMAÑO | 167 cm × 116 cm | |

| LOCALIZACIÓN | National Gallery de Londres, Londres, |

|

| [editar datos en Wikidata] | ||

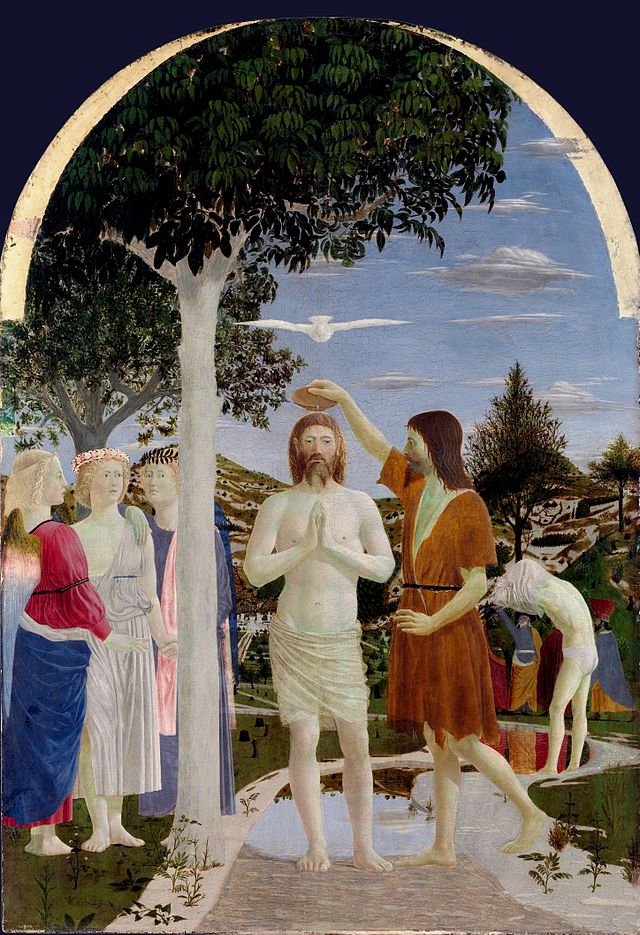

El bautismo de Cristo es uno de los cuadros más conocidos del pintor italianoPiero della Francesca. Está realizado al temple sobre tabla. Mide 167 cm de alto y 116 cm de ancho. Se calcula que se realizó en torno al año 1450, encontrándose actualmente en la National Gallery de Londres, Reino Unido.

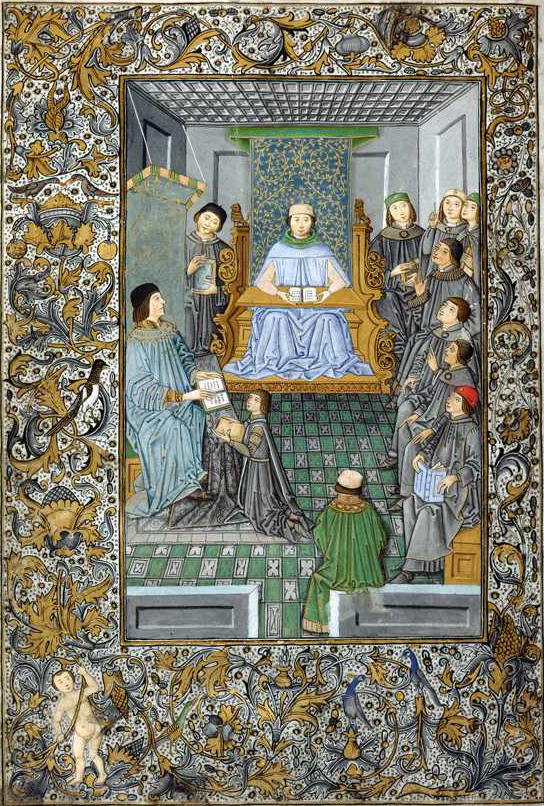

Su datación es controvertida, hasta el punto de que algunos la consideran la primera obra de Piero. Algunos elementos iconográficos, como la presencia de dignatarios bizantinos en el fondo, hacen que se sitúe la obra en torno a 1439, año del Concilio de Basilea-Ferrara-Florencia en el que se reunificaron efímeramente las iglesias de Occidente y Oriente. Otros datan la obra más tarde, en torno al 1460.

Está constituido por dos grandes planchas de álamo al veteado vertical, con las proporciones de la sección áurea (la altura es igual a la largura x V¯2). El eje medio genera una partición calculada, aunque no simétrica. El árbol a la izquierda que divide el cuadro en proporción áurea, tiene más valor como cesura que el grupo central.

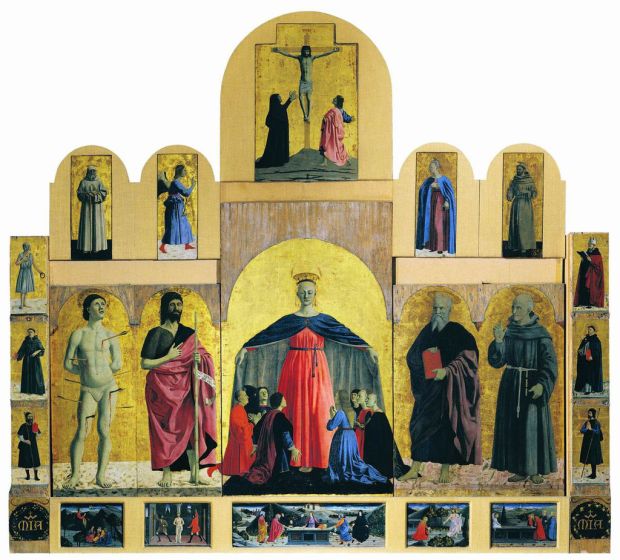

Es la parte central de un tríptico, destinado al altar central de la Iglesia de San Juan en Borgo San Sepolcro.1 Las otras partes del retablo se conservan hoy en la catedral, obra de Matteo di Giovanni.2

Esta es una de las obras tempranas más famosas de su autor.

Análisis

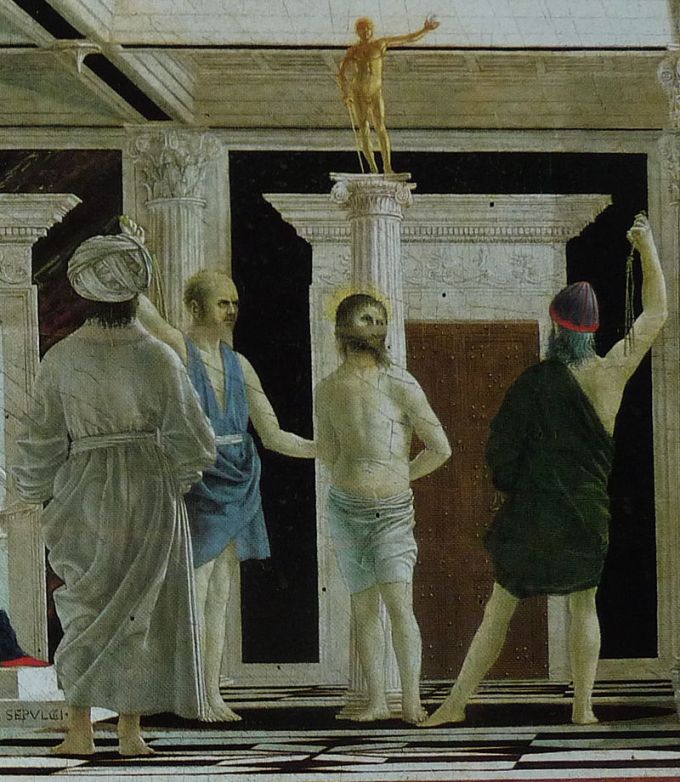

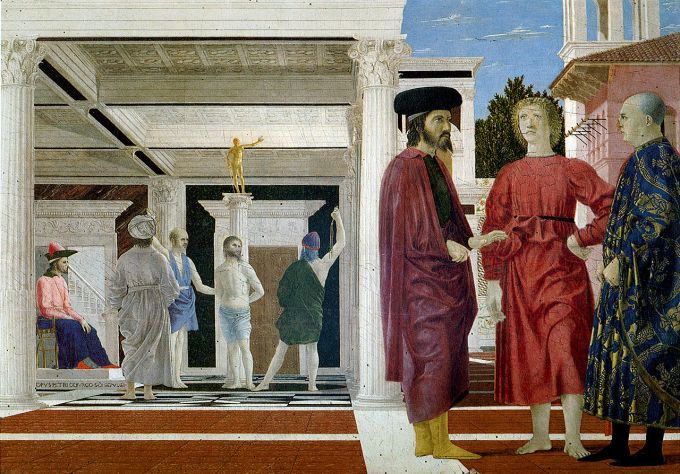

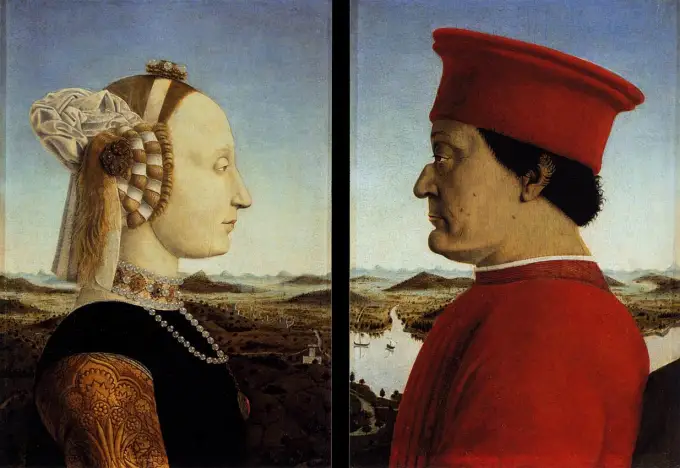

Otros cuadros de Piero Della Francesca

POLÍPTICO DE SAN ANTONIO

DÍPTICO DEL DUQUE DE URBINO

EL BAUTISMO DE CRISTO

REPRESENTACIÓN:

Representa el momento en que Cristo, situado en el centro de la composición, es bautizado porSan Juan Bautista, ubicado a la derecha. El cuerpo de Cristo, forma un eje vertical en el cuadro que se sitúa entre los tres ángeles a su derecha y San Juan Bautista a su izquierda. Cada uno de los ángeles tiene un peinado, color y pose distintos, lo que refuerza simbólicamente la presencia de la Santísima Trinidad. Los tres ángeles, vestidos de colores diferentes, en contraste con la norma iconográfica, no sostienen los vestidos de Cristo sino que se agarran la mano, en señal de concordia: muchos críticos ven en ellos las celebraciones tenidas en aquellos años en Florenciapara la unificación de la iglesia occidental con la oriental (entre de ser uno de los temas mayormente discutidos fue aquel de la Trinidad, en la que había habido un papel distinguido el camaldulense Ambrogio Traversi).

Este simbolismo parece verse reforzado por la presencia, justo a la derecha del neófito o catecúmeno que va a ser bautizado, de unos dignatarios vestidos con trajes bizantinos, que era la vestimenta que entonces se asimilaba a los trajes de la Antigüedad. Uno de ellos señala, con la mano, al Espíritu Santo descendiendo sobre el Cristo bajo el aspecto de una paloma que despliega sus alas, pudiendo ser una prefiguración de la cruz.

Debajo de Cristo corren las aguas del río Jordán. El río traza una S invertida, motivo recurrente en las composiciones de Piero Della Francesca (el corte en la ropa de la Madonna del parto) como los personajes sólidos, bien asentados sobre sus pies.

En la composición se encuentra una destacable alusión a la perspectiva, fundamental en la obra de Piero, ya que las propias figuras conforman el espacio donde se asientan. La composición se basa en un cuadrado y un círculo, representando el cuadrado la tierra y el círculo el cielo.

Es una pintura al aire libre que realiza la unión de dos elementos: el paisaje y los personajes. El paisaje se ha identificado como propio de la región de Umbría. El centro del semicírculo superior está ocupado por la paloma (símbolo del Espíritu Santo), la concha sostenida por elBautista y la figura de Cristo.

Las figuras están sabiamente interpretadas, obteniendo un marcado acento volumétrico gracias al empleo de la luz y resaltando el aspecto escultórico y anatómico de los personajes. La luz cenital anula las sombras, dando homogeneidad a toda la composición. Las tonalidades no son muy vivas, al bañar las figuras con esa luz blanca y uniformemente distribuida.

Se observa un esmerado detallismo que puede apreciarse en la meticulosa atención que el artista presta a detalles secundarios como las hojas de los árboles y el reflejo de las montañas en el agua, fruto de la observación de la naturaleza. Este paisaje rico y diferenciado es inusual en lapintura florentina de la época.3 Hay que precisar que el tronco del árbol y las orillas del río no conservan sus colores originales, al haber sido sometidos a una limpieza agresiva. El tono ahora visible corresponde a una capa pictórica inferior, que quedó al descubierto al eliminarse los tonos finales.

Hay un paralelismo entre distintas partes del cuadro. Así, la paloma del Espíritu Santo es similar a las nubes sobre el fondo; Jesús se parece al blanco tronco del árbol que hay junto a él, observándose que los árboles se van oscureciendo conforme se alejan de Cristo; el motivo de la línea curva se presenta en las eses del río Jordán y en la postura del joven que va a ser bautizado que está a la derecha.

Finalmente, para testimoniar la síntesis geométrica que tanto amaba Piero della Francesca, Juan Bautista forma con el brazo derecho y con la pierna izquierda don ángulos de la misma amplitud.

___________________________________________________________________

Comentarios

- Según Roberto Longhi: «Estos personajes serían sacerdotes judíos contemporáneos del Cristo.»

- Según André Chastel: «En realidad son testigos bizantinos directamente tomados de los grupos reunidos en Florencia para el Concilio… ellos aportan así la prueba de que hay un solo bautismo puesto que estos personajes son griegos.” Griego o latino, el bautismo es idéntico y también válido. » (L’Italie et Byzance, Editions de Fallois, París, p.255).

- Según P. Rotondi, del Museo del Vaticano, Piero della Francesca realiza aquí la primera pintura “al aire libre”, en la que «la agilidad del pincel y la ausencia de retoques prueban que el cuadro se hizo de un solo trazo».4

Fuente: