William Caxton (ca. 1415~1422 – ca. marzo de 1492) fue un mercader, diplomático, impresor y escritor inglés. Caxton llevó la primera imprenta a Inglaterra y fue el primer impresor del país (sus colegas en Londres eran alemanes, neerlandeses o franceses). Imprimió y editó más de cien libros, la mayoría traducciones de obras francesas. Algunas de las más importantes obras impresas por Caxton fueron La muerte de Arturo, de Thomas Malory, y los Los cuentos de Canterbury, de Geoffrey Chaucer.

Primeros años, como comerciante

La fecha exacta de su nacimiento se desconoce. Se sabe que Caxton nació en la campiña de Kent entre 1415 y 1422 y fue a Londres a trabajar. En 1438 se le ubica como aprendiz de comerciante de telas, en el taller de Robert Large, quien sería alcalde de Londres al año siguiente. Large murió en 1441, y en 1446 Caxton se marchó a Brujas, centro principal del comercio europeo de textiles.1 En Brujas, Caxton progresó en el comercio textil y destacó entre sus compatriotas afincados en el continente. Obtuvo en 1463 el cargo de Gobernador del gremio inglés de comerciantes pacotilleros2 en los Países Bajos. Hacia 1470, Caxton se encuentra al servicio deMargarita de York, duquesa de Borgoña y hermana del rey de Inglaterra Eduardo IV. Es probable que Caxton fuera el asesor financiero de la duquesa.

Como impresor

Caxton comenzó a interesarse por la literatura a finales de la década de 1460. En marzo de 1469, Caxton empezó a traducir el libro Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, de Raoul Le Fèvre. Caxton abandonó la tarea, desanimado por su pobre dominio del francés; pero la reanudó a petición de la duquesa Margarita y terminó la traducción en 1471.

En Brujas

Caxton cambió de residencia varias veces entre Flandes, los Países Bajos y Alemania. Cuando residía en Colonia, entre 1470 y 1472, Caxton entró en contacto con la naciente industria de la impresión y aprendió el arte de imprimir. Según el propio Caxton, se decidió por aprender a imprimir para evitar el cansancio que sufrían sus ojos y su mano con el arduo trabajo de la traducción.3

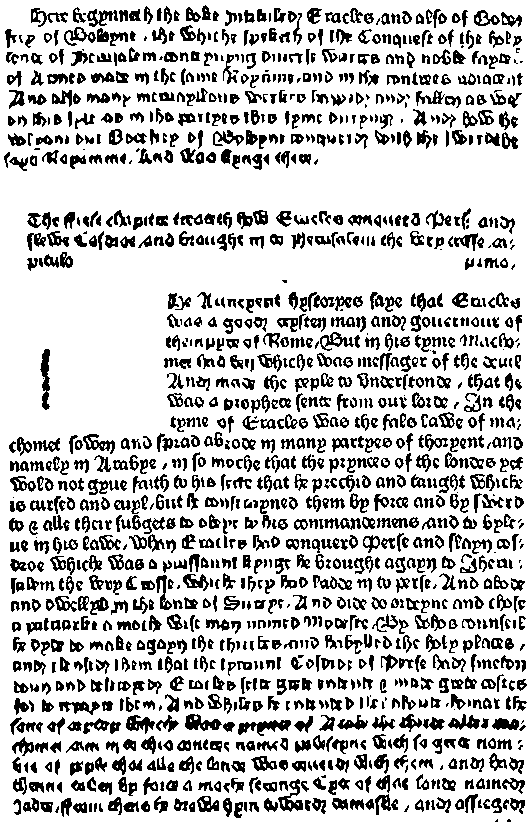

Facsimile de la primera página de Godefrey of Boloyne, impresa por Caxton en Londres, 1481.

Inmediatamente compró una imprenta con dos juegos de tipos móviles,4 y en 1474 volvió a Brujas a establecer un taller de impresión. Allí, se asoció con Colard Mansion, un afamado copista e ilustrador de códices. El primer libro impreso por Caxton, al año siguiente, fue la traducción que él mismo realizó del libro Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye.5 En la misma ciudad, Caxton publicó otros cinco libros, incluyendo la misma obra de Le Fèvre en francés. De los cinco, solamente uno de ellos era en inglés, The game and playe of the chesse, publicado el 31 de marzo de 1475. Este libro era una traducción de dos versiones francesas de De ludo scaccorum, obra del dominico Jacobo de Cessolis, de alrededor del año 1300.

En Londres

Al regresar a su país en 1476, Caxton fundó una imprenta en los terrenos de laAbadía de Westminster. A partir de entonces, su única ocupación fue el imprimir y editar libros, muchas veces escribiendo los prólogos o epílogos de los mismos. Su primera impresión en Inglaterra fue, al parecer, una Indulgencia otorgada por el abadde Abingdon.

La impresión está fechada el 13 de diciembre de 1476.6 Al año siguiente, Caxton publicó Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres (Dichos de los filósofos, el 18 de noviembre), escrito por el cuñado del rey, Anthony Woodville, Conde de Rivers, quien había hecho la traducción del francés de Guilliaugme de Tignonville. Los Dichos de los filósofos pasaron por ser el primer documento impreso por Caxton en Inglaterra, hasta el descubrimiento de la Indulgencia de 1476. Ese mismo año, Caxton imprimió también una traducción del francés Histoire de Jason, de Raoul Le Fèvre.

La primera edición de Caxton de Los cuentos de Canterbury apareció en 1478. La edición representaba el trabajo más extenso de Caxton hasta el momento, pues constaba de 374 folios. Cinco años más tarde, reeditaría la obra, añadiéndole más de veinte xilografías y con un texto revisado. Aún en 1478, Caxton imprimió otra obra de Chaucer, la versión de este último de Deconsolatione philosophiae, de Boecio.

El libro más voluminoso que Caxton editó fue La leyenda dorada, en 1483. El libro, de 600.000 palabras y 448 folios impresos a doble columna, era una traducción que el propio Caxton había hecho del texto de Jacobo de Vorágine. La traducción se basaba en una versión francesa de Jean de Vignay, y Caxton se tomó la libertad de añadir las vidas de 25 santos que no estaban incluidas en dicha versión. La obra está generosamente ilustrada, 19 de sus xilografías ocupan una página entera.

La muerte de Arturo fue publicada por Caxton el último día de julio de 1485. El autor, Sir Thomas Malory, había muerto catorce años antes, y Caxton organizó la voluminosa obra de la manera que mejor le pareció, dividiéndola en 21 Libros y 507 capítulos.7 Además, Caxton hizo una revisión completa del texto, añadiendo rúbricas que describían la acción, al principio y final de cada capítulo.

En su imprenta, Caxton produjo romances caballerescos, trabajos de autores clásicos e historias romanas e inglesas. Los libros que Caxton imprimía eran favorecidos por las clases altas del reino, por lo cual el apoyo financiero que Caxton recibía de la aristocracia y la nobleza era importante, aunque no indispensable.

Caxton murió en 1492, un año después que su esposa Maude. Fue enterrado en St. Margaret, en Westminster. En 2002, la compañía mediática BBC lo incluyó en la lista de los 100 más grandes ciudadanos británicos de todos los tiempos.8

_____________________________………………………==========================

WILLIAM CAXTON

William Caxton (c. 1415 – c. March 1492) was an English merchant, diplomat, writer and printer. He is thought to be the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England, which he did in 1476. He was also the first English retailer of printed books (his London contemporaries in the same trade were all Flemish, German or French). In 2002 he was named among the 100 Greatest Britons in a BBC poll.[1]

Biography

Early life

The printer’s device of William Caxton, 1478

William Caxton’s parentage is uncertain. His date of birth is unknown, but records place it in the region of 1415–1424, based on the fact his apprenticeship fees were paid in 1438. Caxton would have been 14 at the date of apprenticeship, but masters often paid the fees late. In the preface to his first printed work, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, he claims to have been born and educated in the Weald of Kent. Oral tradition in Hadlowclaims that Caxton was born there; the same withTenterden. One of the manors of Hadlow was Caustons, owned by the Caxton family. A house in Hadlow reputed to be the birthplace of William Caxton was dismantled in 1436, and incorporated into a larger house rebuilt in Forest Row, Sussex.[2]

Caxton was in London by 1438, when the registers of the Mercers’ Company record his apprenticeship to Robert Large, a wealthy London mercer, or dealer in luxury goods, who served as Master of the Mercer’s Company, and Lord Mayor of Londonin 1439. After Large died in 1441, Caxton was left a small sum of money (£20). As other apprentices were left larger sums, it would seem he was not a senior apprentice at this time.

Printing and later life

Facsimile of page 1 of Godefrey of Boloyne, printed by Caxton, London, 1481. —- The Prologue, at the top of page, begins: Here begynneth the boke Intituled Eracles, and also Godefrey of Boloyne, the whiche speketh of the Conquest of the holy lande of Jherusalem.(the blank space on this page was for the insertion by hand of an illuminated initial T)

He was making trips to Bruges by 1450 at the latest and had settled there by 1453, when he may have taken his Liberty of the Mercers’ Company. There he was successful in business and became governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London. His trade brought him into contact with Burgundy and it was thus that he became a member of the household of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, the third wife of Charles the Bold and sister of two Kings of England,Edward IV and Richard III. This led to more continental travel, including travel toCologne, in the course of which he observed the new printing industry, and was significantly influenced by German printing. He wasted no time in setting up a printing press in Bruges, in collaboration with a Fleming, Colard Mansion, and the first book to be printed in English was produced in 1473: Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye,[3] a translation by Caxton himself. His translation had become popular in the Burgundian court and requests for copies of it were the stimulus for him to set up a press.[4] Bringing the knowledge back to England, he set up a press at Westminsterin 1476 and the first book known to have been produced there was an edition ofChaucer‘s The Canterbury Tales (Blake, 2004–07). Another early title was Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres (Sayings of the Philosophers), first printed on 18 November 1477, translated by Earl Rivers, the king’s brother-in-law. Caxton’s translation of theGolden Legend, published in 1483, and The Book of the Knight in the Tower, published in 1484, contain perhaps the earliest verses of the Bible to be printed in English. He produced the first translation of Ovid‘s Metamorphoses in English.[5]

Caxton produced chivalric romances (such as Fierabras), the most important of which was Sir Thomas Malory‘s Le Morte d’Arthur, classical works and English and Roman histories. These books appealed to the English upper classes in the late fifteenth century. Caxton was supported by, but not dependent on, members of the nobility and gentry.

Death and memorials

Caxton’s precise date of death is uncertain, but estimates from the records of his burial in St. Margaret’s, Westminster, tend to show that he died near March of the calendar year 1492. However, George D. Painter makes numerous references to the year 1491 in his book William Caxton: a biography as the year of Caxton’s death, since according to the calendar used at the time (24 March being the last day of the year), the year-change hadn’t happened yet. Painter writes, “However, Caxton’s own output reveals the approximate time of his death, for none of his books can be later than 1491, and even those which are assignable to that year are hardly enough for a full twelve months’ production; so a date of death towards autumn of 1491 could be deduced even without confirmation of documentary evidence.” (p. 188)

In November 1954 a memorial to Caxton was unveiled in Westminster Abbey by J.J. Astor, chairman of the Press Council. The white stone plaque is on the wall next to the door to Poets’ Corner. The inscription reads:

- “Near this place William Caxton set up the first printing press in England. This stone was placed here to commemorate the great assistance rendered to the Abbey Appeal Fund by the English speaking press throughout the world.”[6]

Fuente: